Anyone who knows me understands that I consider ordinary cooking regalia– and sometimes food itself–primarily for its artistry and sentimental value. So while I was delighted to come across this colorful cutlery display in a Marrakesh souk, I did not sample any of the food or drink. (At least two fellow travelers did, and came deeply to regret it.)

Like my mother, I find colorful kitchen kitsch irresistible. I have a bat-shaped bottle opener, Los Pollos Hermanos glassware, neon lime spaghetti tongs shaped like a Simpsons alien, and the pièce de résistance: my brother’s gift of a trivet shaped like a chalk outline at a crime scene.

He gets me.

I have painted many kitchen items that rarely–and sometimes never–have been used to hold food, but have traveled with me from sparsely-used kitchen to kitchen. These include birthday plates for my children, and a platter I made for my stargazing husband when we moved into the home of his dreams. And a bowl I painted for him one Christmas, when his whispers were not so distant. I adorned it with Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s words: “The sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out; At one stride comes the dark; With far-heard whisper, o’er the sea; Off shot the spectre-bark.”

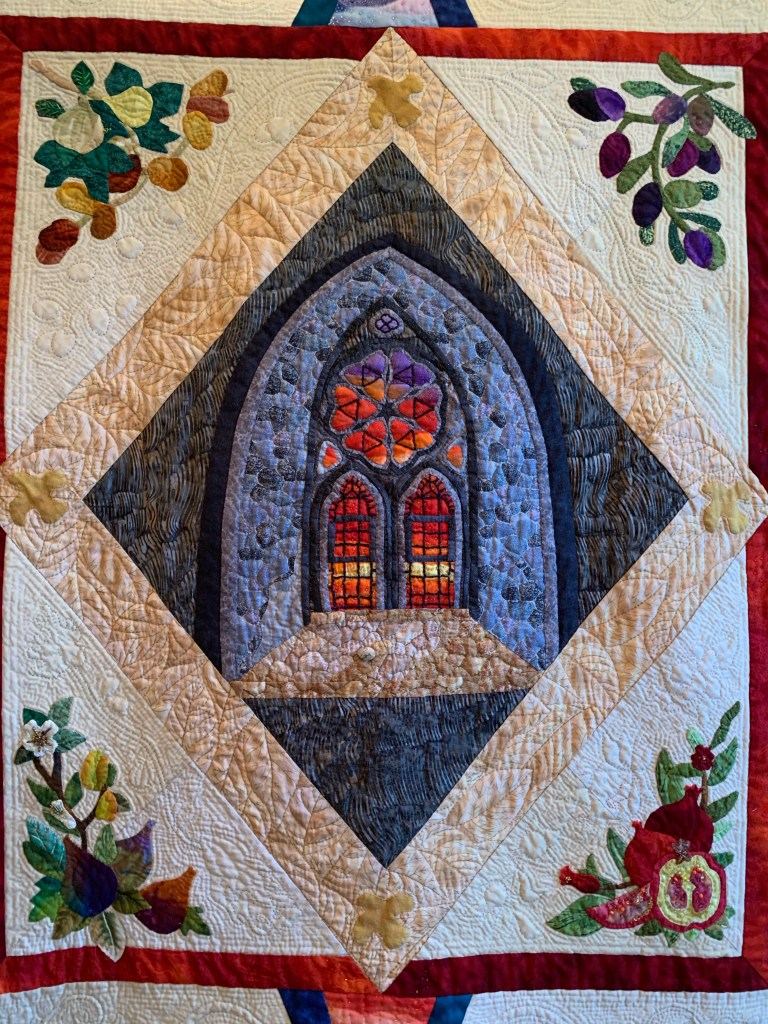

And while authentic fruits and vegetables rarely meet their fates in my own kitchen space, I always find room there to memorialize them in fabric, in eternal perfect bloom.

I married into a family in which the kitchen was, and remains, a hub of family and love. And food. So much food.

As our children grew, we would gather almost every Sunday with three of my husband’s sisters’ families at their parents’ house for holidays, walks to playgrounds, games and conversation and feasts.

Each of more than a dozen grandchildren had favorite hors d’ouevres and main dishes and desserts, and their Grandma Jackie tirelessly made their culinary dreams come true. She even drafted for me two favorite family recipes that I eventually was able to execute myself without structural kitchen disaster or serious medical repercussions.

Tables continue literally to groan on a daily basis in my sisters-in-laws’ homes. Although my husband mightily manned the grill when weather allowed, our own assorted refrigerators largely became backdrops for kitschy magnets which held our children’s artwork. (I wonder if it is a coincidence that he eventually decided to get a refrigerator with a paneled door that was impervious to my random decorative explosions.)

I grew up in very different spaces, where kitchens came with the apartment or home, tastes were picky and internally inconsistent, and family meals were rare. There could not have been a more stark contrast between bounty and frugality than the space between my husband’s and my views of food and its preparation and consumption. Stylistically, it was like Quaker versus Baroque.

My father had a habit, which I hope was unique, of combining disparate things he found while staring at cabinet shelves and presumably thinking about entropy. He had grown up making due with what he had and wasting nothing. The dregs of an ancient gin bottle would find themselves mixed with equally world-weary vodka, perhaps in quixotic hope that they might merge into something palatable, or at least non-injurious if eventually consumed.

His peculiar kitchen habits may have informed a phase in which my children vied for bragging rights in contests involving decoratively consolidating leftovers.

This is a roundabout way of saying that my richest kitchen memories only rarely involve food, and always link to other senses. My mind has convinced me that nothing ever tasted as sublimely delicious as the August tomatoes my mother brought from a nearby farm when I was recovering after my first son’s birth. Or the dense quadruple-chocolate cake my father-in-law brought after my first daughter’s winter birth, when I sat with her and her brothers in the irreplacable warmth of our first house’s woodstove.

I still have a coffee mug bought during our honeymoon in Quebec, which has been safeguarded from kitchen use and has not changed at all during the intervening decades. I wish I had taken a picture of the tall ceramic mugs I no longer have, handpainted with swirls of autumnal green and gold. They were in a coffee shop in Perkins Cove that now has gone missing, too. The set was the next-to-last corporeal gift my husband gave me. In my first detective novel, it was no coincidence that my grieving heroine was undone when she dropped its doppelgänger: she “closed her fingers into a white-knuckled fist over the corpus of its only remaining large shard, with its tauntingly intact handle. The rim from which [her husband] had sipped just months earlier was gone, gone away.”

No treasured household gift stands, or falls, alone.