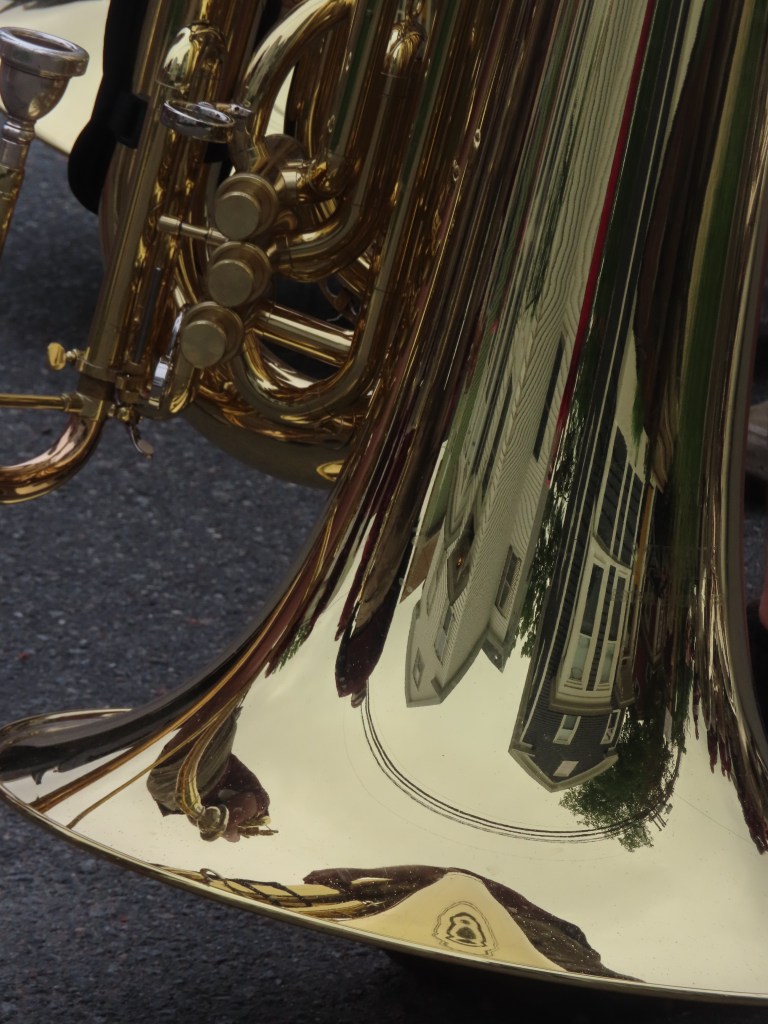

In the brief light between June storms in New Hampshire, lyrical liquid gold held four centuries’ reflected and refracted images. It was the Portsmouth Clipper Marching Band‘s 400th birthday. Alums from the past five decades–including some who had marched during the 350th band birthday celebration–played past colonial and Victorian and modern homes on Market Street.

Elongated fragments. Shards. Parts and particles of the past.

Pieces of our histories, our hopes, and our uncertain futures can filter into both our waking and sleeping selves.

And, as with most things, John Hiatt wrote (and sang) it best: “The missing pieces are everywhere.”

There are at least two very different ways of considering the sentiment. We perpetual pessimists see the fissures, the empty spaces from which parts have gone missing. The misshapen space that taunts us after that last errant jigsaw puzzle piece has somehow escaped its box. The sub-zero empty harbor after summer’s celebrants have hunkered down for another winter. Holes in our hearts and homes.

But there is another way to look at it: to see all around us the melifluous, misfit missing pieces. All the gold that stays.

Not to restore what was, but to reconfigure it, piece by piece, row by row. Kintsugi of sorts. Never the same, but with its own beauty, born of time and healing and adapting as best we can to whatever comes our way.