It might seem like an ordinary spot.

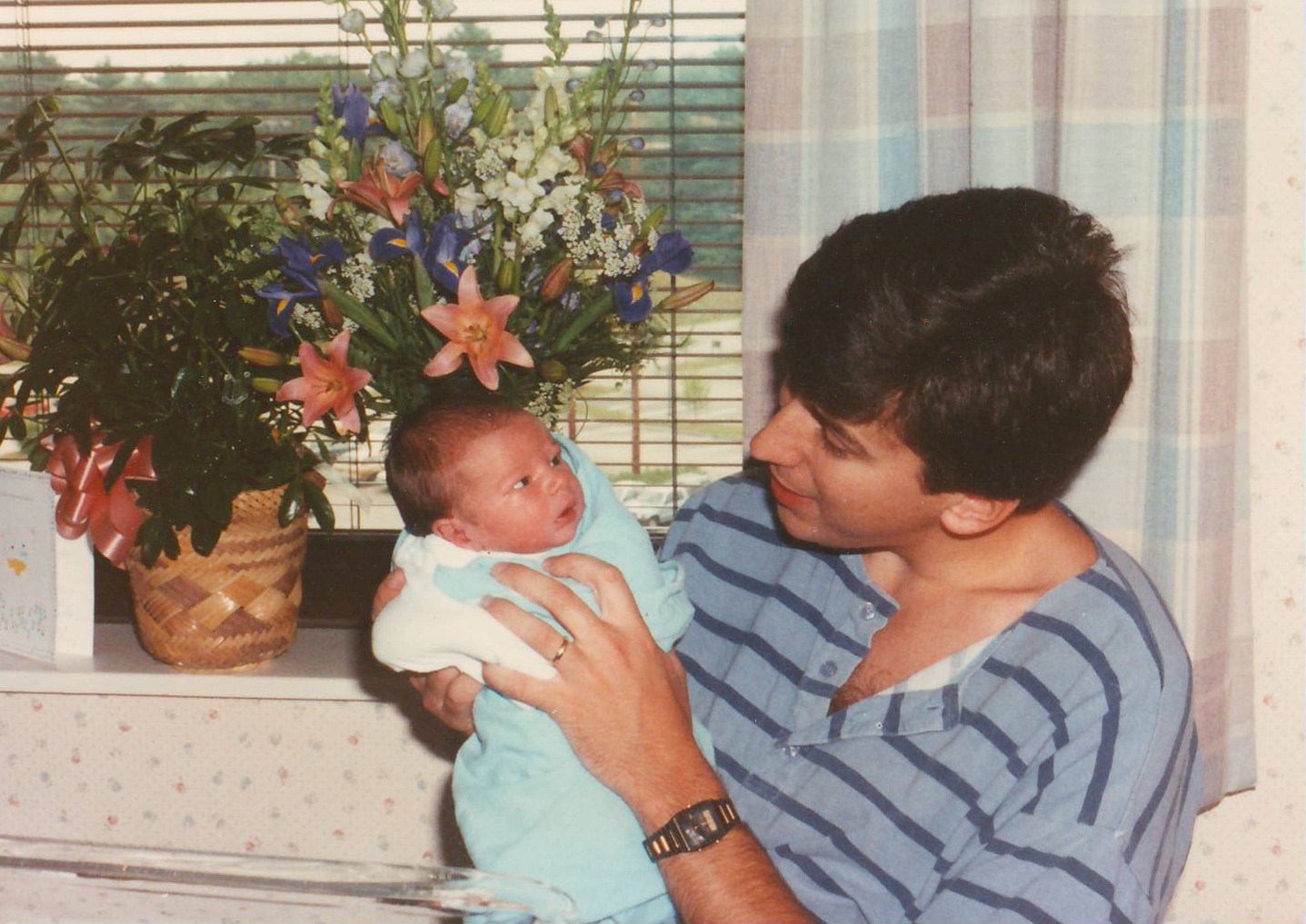

Now, as then, one rock’s broad surface comfortably seats a man over six feet tall, allowing him to look up at the much slighter young woman facing him under a Long Nights Moon.

You faced the moon and I faced you. . . .

Technically I have been alone when revisiting the spot, in mind or body. Even now, few couples would make the rocky climb on a December night. Its most perilous stretches had no guard rails then. Hemmed by poison ivy and washed by surf, scattered signs warned of the trek’s perils, beginning with the precipitous drop from unsteady earth to roiling sea.

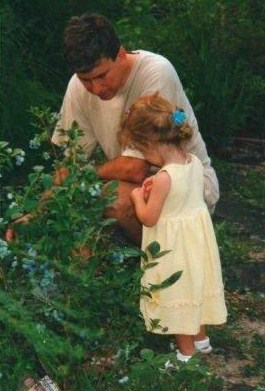

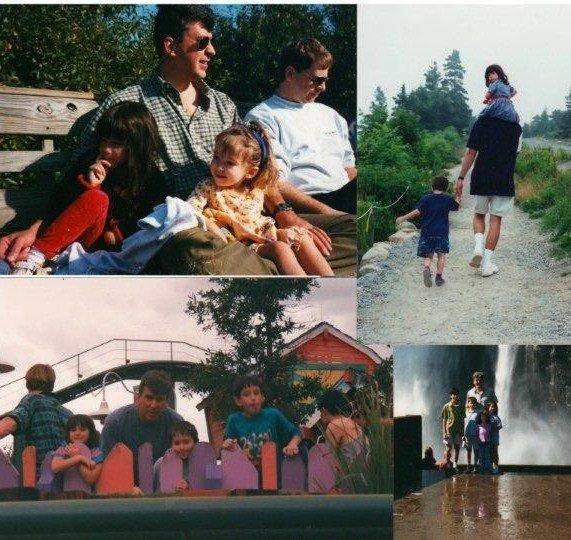

And we talked about the future we hoped to have and came to be.

From the narrow, rutted path’s highest point, where the young man sits and she stands, an overlook offers a panoramic view of the horizon, bracketed by ridged limestone shelves angled into the seabed, as glaciers had decreed.

The young man’s vision is razor-sharp, as it will remain all his life. Beyond his moonlit partner he sees a swath of inky, noisy ocean punctuated only by a rocky outcropping miles from shore. There, tiny Boon Island personifies the word “barren.” No less a luminary spirit than poet Celia Thaxter, of New Hampshire’s convivial close-knit Isles of Shoals and their blooming gardens, is said to have once described Boon Island as “the forlornest place that can be imagined.”

The young man’s vision is razor-sharp, as it will remain all his life. Beyond his moonlit partner he sees a swath of inky, noisy ocean punctuated only by a rocky outcropping miles from shore. There, tiny Boon Island personifies the word “barren.” No less a luminary spirit than poet Celia Thaxter, of New Hampshire’s convivial close-knit Isles of Shoals and their blooming gardens, is said to have once described Boon Island as “the forlornest place that can be imagined.”

Despite its size and solitude, its uneven granite has drawn in and grounded ships over the centuries. And more than one sturdy stone lighthouse there has been storm-toppled into the sea, rearranging itself into mazes on the ocean floor.

The distant toothpick of the most recently rebuilt lighthouse is in fact New England’s tallest. Standing at strict attention atop the granite pile where nothing grows, it laconically cycles its pure white light, lest another insufficiently attentive traveler come too close.

Compared to its nearest neighbor, the gaudily scarlet-strobing, holiday-bedazzled and aggressively photographed Nubble Lighthouse, one would have to concentrate very carefully to commit this shy slender cousin to pixels or film. When one does, the tiny island itself often appears to be hovering above the water, as if it is present both as we know it to be and also its own ghost.

At this spot my husband and I shared at the cliff’s edge, the only sound likely to be heard during any season gently floated upwards. Thousands of water-smoothed stones companionably clattered as waves cycled below. They mingle and chatter as each wave washes over them and recedes, resettling their companions only slightly as they all await the next incoming wave. The sound becomes less mellifluous only in the most ferocious storms–the rare, intense storms we sometimes do not sense are coming, and which might fell even the most dependable beacons.

It is no coincidence that this single quotidian patch of earth and rock snuck itself into my subconscious memory, and in turn has played a role in both my fiction and non-fiction.

My husband died almost twelve years ago, but I will always find him–and our younger selves and our future children–in this spot, at least as present as the rocky shore and surrounding sea, and the seagulls who pause to quietly survey the rising sun along with me.

The young man’s vision is razor-sharp, as it will remain all his life. Beyond his moonlit partner he sees a swath of inky, noisy ocean punctuated only by a rocky outcropping miles from shore. There, tiny Boon Island personifies the word “barren.” No less a luminary spirit than poet Celia Thaxter, of New Hampshire’s convivial close-knit Isles of Shoals and their blooming gardens, is said to have once described Boon Island as

The young man’s vision is razor-sharp, as it will remain all his life. Beyond his moonlit partner he sees a swath of inky, noisy ocean punctuated only by a rocky outcropping miles from shore. There, tiny Boon Island personifies the word “barren.” No less a luminary spirit than poet Celia Thaxter, of New Hampshire’s convivial close-knit Isles of Shoals and their blooming gardens, is said to have once described Boon Island as