Every living and growing thing is a work in progress, as are most inanimate and many unseeable things. Tulip bulbs and time-smoothed rocks. Reflections, both visible and internal. A trip by land or sea or sky. Quilts , from the sketching to the sewing process. Sunrise. Anger. Taste in art and novels. Betrayal and trust, both in the building and in the breach.

Landscapes and visitors to them. Altitude and attitude.

Hope and regret and resignation.

Memories. Love.

Lunch.

Even when something’s done and dusted–including long after I’ve pressed “publish”–everything I write remains a work in progress. When I revisit an old post, or a brief I filed decades ago, I often wince at something that could have been better said.

Each post I’ve made in the past many months has required a scandalous number of revisions–not because of a change in the way I write, but because of changes in me. (Although I suspect that is a chicken-and-egg construct for most people who write).

The writer I am in the moment is never the writer I was in the past. Sometimes, for better and worse, I hardly recognize prose as mine. I’m occasionally pleasantly surprised. (More often, I think, “How could I have missed that mistake when I read my draft aloud . . . four times?”)

Every living and growing thing is a work in progress, as are most inanimate and many unseeable things. Tulip bulbs and time-smoothed rocks. Reflections, both visible and internal. A trip by land or sea or sky. Quilts , from the sketching to the sewing process. Sunrise. Anger. Taste in art and novels. Betrayal and trust, both in the building and in the breach.

The quilts I’ve sewn since I was ten are, by their nature, works in often reductive progress. The better loved a baby quilt, the more it tends to emerge from its recipient’s childhood in a very different and diminished physical state (not unlike its seamstress). It begins and ends in pieces.

The process of handmaking a quilt, followed by a child’s enthusiastic use of it, is like a Riddle of the Sphinx writ in 100% cotton prints. The binding at the quilt’s edges–always the final touch when making it–is almost always the first to go. Its tightly woven threads are worn away by tiny hands grasping it for comfort. Entire brightly-colored applique shapes sometimes follow suit, fading and letting go like petals once they have been loved back to exhausted pieces. The hand-stitched threads that secured them can only take so much love and laundering.

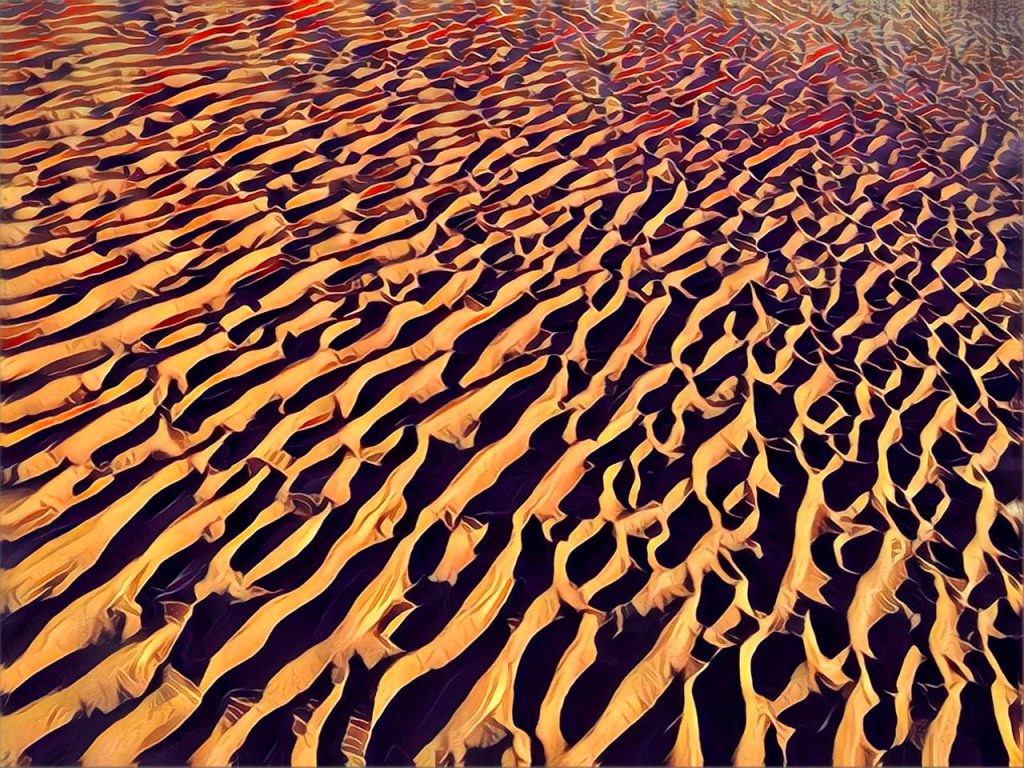

This goes for my photographs, too, in a way. I now take photos in somewhat less absurd quantities than I acquire fabric. My early landscape and seascape photos were . . . not good. I tended to emulate my longtime Deering camp friends’ band motto–“Quality through volume.” But along the way, I grew from sheer practice to be able to frame shots. To catch the ephemeral when it was willing to be caught. To wait patiently, no matter what was buzzing and slithering and stinging nearby . To appreciate what was temporarily in my sight, and that a rushed shot would not enhance my chances of preserving something special.

This morning was summer-steamed, shrouded in deep gray mist. But I thought I spotted a visitor to a darkened house just off a very busy main road. From a distance, I quietly zoomed in and took a single photo.

I may still have work to do, but the fawn posed perfectly before loping away.

I couldn’t have improved on it.